About The Book

The Book

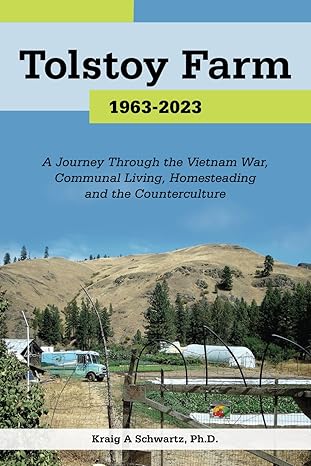

Tolstoy Farm: 1963-2023

A Journey Through the Vietnam War, Communal Living, Homesteading and the Counterculture

Tolstoy Peace Farm was founded as a training center in Eastern Washington state for peace activists. After three or four years it was just known as Tolstoy Farm, which still survives today. Huw Williams, the Farm’s founder, sought to develop a community that would embrace love, non-violence and simple living as its foundation. Influenced by 19th century intentional communities and by the Christian anarchist ideas of Leo Tolstoy, Williams initially recruited fellow peace niks, all of whom were “war babies” or born in the 1930s, to help build this new community. Everyone was welcome and no one could be turned away. All decisions were made by consensus. During the first three years the community grew slowly. They grew food, lived collectively and participated in peace activities in Spokane, Seattle and San Francisco.

In 1966 “baby boomers” began to arrive, and they brought marijuana with them. Local authorities learned of this and raided the Farm. Seventeen Tolstoy Farmers were arrested and five of those Farmers were charged with felonies and jailed for six months or more. The bust was a major blow, as half of the peace nik founders chose to leave. Yet, more and more “boomers” began to arrive, prompted by the Vietnam War and what began to be labeled the “counter culture.” By 1972 between 80-100 people lived at the Farm, including twenty-five children. But, the Farm was again busted, one of the first chapters in Nixon’s “War on Drugs.” A posse of more than 50 cops invaded the Farm. Ten people were arrested; nine were charged, all of whom had to stand trial. At trial, with their freedom challenged, Tolstoy Farmers expressed their solidarity and fought back in the courtroom, tearing flags off the wall, breaking up furniture and physically challenging the police. Little marijuana was found; the search warrant was defective; very light sentences were dispensed; it was an embarrassment to the authorities. The sheriff resigned. The Farm was never busted again.

As the Vietnam War ended the momentum of the counterculture slowed. By the late 1970s the Farm population declined significantly, but life went on for most Farmers. They built houses, grew food, raised children and built a school. Yet, by the early 1990s, the the Farm was in decline. However, a new generation of people began to arrive. The new arrivals, in collaboration with seasoned Farmers, worked to expand Tolstoy Farm Gardens. By the Farm’s 2003 40th reunion commemoration, Tolstoy Farm Gardens had rebranded the farm. It was no longer known as a hippie commune, but became the signature supplier of organic produce for farmers’ markets and homes in Spokane. Operated on the principles of equality and self management, TFG before covid employed about one fourth of the Farm’s adult population, but in the post-covid era TFG lacks workers and has had to cut back production.

So Tolstoy Farm is at a critical juncture. Will it survive? If so, what kind of place will it be in the future, an intentional community united by a common purpose or land with a disparate population. The land cannot be sold or subdivided. Forty-five Farmers live there today, including four children. People own their homes, but not the land. There is no longer an emphasis on simple living and and self-sufficiency. It is no longer a collective or an intentional community. It is not the peace farm it set out to be, nor is it the hippie community of the 1970s. Yet, it remains a place of peace and freedom. The future of the Farm depends on the people who live there and the choices they make. New proposals can be blocked by one person. Each resident can voice their opinion on any and all matters. If, for example, a person wishes to admit a a new Farmer, or turn away a provisional resident, or bring about changes to the land tenure system that would allow TFG to expand, then, everyone will have to vote in the affirmative. A very difficult proposition.